READING TIME: 15 minutes

Introduction

Although the importance of a good leader cannot be denied, followers also play an equally important, if often overlooked, role in the success of any group or organization. We believe the strength of any team is in the followers and there can be no leaders without followers, but the vast majority of research to date has focused on the leadership side of this equation. Researchers have only recently given serious consideration to the topics of followers and followership. This research has revealed several interesting questions and findings.

The Changing Expectations for Followers

There was a time in the not too distant past when followership essentially meant, “be quiet and do whatever I tell you to do.” Followers were expected to keep their heads down, put in an honest days work, and only spoke up when asked. Leaders used to have all the power in these hierarchical relationships, but this is no longer the reality facing many organizations. Over the past forty years employers’ expectations for work have changed and they now want more out of their employees than paying them to be a cog in a machine. In addition, because of the successive generations entering the workforce, rising education levels, globalization, the flattening of organizations, and an increased willingness to change careers and companies, employees have come to understand they can add more value doing meaningful work. The better employees are attracted to jobs that make a difference to customers, fellow employees, or the communities they live in and they are much more willing to raise objections when they feel inhibited from making that difference. These cultural changes regarding work have changed so dramatically that even the classic leader-follower organization, the United States military, has fundamentally changed how officers lead and treat their soldiers.

It may be the devil, or it may be the Lord, but you’re gonna have to serve somebody.

– Bob Dylan

Everyone is a Follower

Virtually everyone is a follower at some point in his or her life. And perhaps more importantly, anyone occupying a position of authority plays a followership role at times, as first-line supervisors report to mid-level managers, mid-level managers report to vice-presidents, vice-presidents report to CEOs, CEOs report to Boards of Directors, etc. This being the case, followership should be viewed as a role, not a position. It is worth keeping in mind that some jobs have clear leadership requirements; virtually all jobs have followership requirements. Given that the same people play both leadership and followership roles, it is hardly surprising that the values, personality traits, mental abilities, and behaviors used to describe effective leaders can also be used to describe effective followers.

There are times when situational demands require that individuals in formal followership roles step in to leadership roles. For example, a sergeant may take over a platoon when her lieutenant is wounded in battle, a volunteer may take over a community group when the leader moves away, a software engineer may be asked to lead a project because of their unique programming skills, or team members can be asked to make decisions about team goals, work priorities, meeting schedules, etc. That being the case, those followers who are perceived to be the most effective are those most likely to be asked to take a leadership role when opportunities arise. So understanding what constitutes effective followership and then exhibiting those behaviors can help improve a person’s career prospects. Effective followership plays such an important role in the development of future leadership skills that freshman at all the United States service academies (the Air Force Academy, West Point, Annapolis, and the Coast Guard and Merchant Marine Academies) spend their first year in formal follower roles.

Traveling down the path set by the service academies, it may well be that the most effective people in any organization are those who are equally adept playing both leadership and followership roles. There are many people who make great leaders but ultimately fail because of their inability to follow orders or get along with peers. And there are other people who are great at following orders but cause teams to fail because of their reluctance to step up into leadership roles. The more people develop leadership and followership skills, the more successful they will be.

Followers Get Things Done

Better followership often begets better leadership.

-Barbara Kellerman, Harvard University

It is important to remember the critical role followers play in societal change and organizational performance. The Civil Rights and more recent Tea Party movements are good examples of what happens when angry followers decide to do something to change the status quo. And this is precisely why more totalitarian societies, such as North Korea, Myanmar, or Iran, tightly control the amount and type of information flowing through their countries. Nothing gets done in organizations without followers, as they are people closest to the customers and issues, creating the products, taking orders, and collecting payments. Research has consistently shown that more engaged employees are harder working, more productive, and more likely to stay with organizations than those who are disengaged. Moreover, ethical followers can help leaders avoid making questionable decisions and high performing followers often motivate leaders to raise their own levels of performance. Wars are usually won by armies with the best soldiers, teams with the best athletes usually win the most games, and companies with the best employees usually outperform their competitors, so it is to a leader’s benefit to surround him or herself with the best followers.

The Psychology of Followership

Although asking why anyone would want to be a leader is an interesting question, perhaps a more interesting question is asking why anyone would want to be a follower. Being a leader clearly has some advantages, but why would anyone freely choose to subordinate his or herself to someone else? Why would you be a follower? Evolutionary psychology hypothesizes that people follow because the benefits of doing so outweigh the costs of going it alone or fighting to become the leader of a group. Twenty thousand years ago most people lived in small, nomadic groups, and these groups offered individuals more protection, resources for securing food, and mating opportunities than they would have had on their own. Those groups with the best leaders and followers were more likely to survive, and those poorly led or consisting of bad followers were more likely to disappear. Followers who were happy with the costs and benefits of membership stayed with the group; those who were not either left to join other groups or battled for the top spots. Evolutionary psychology also rightly points out that leaders and followers can often have quite different goals and agendas. In the workplace, leaders may be making decisions in order to maximize financial performance whereas followers may be taking actions to improve job security. Therefore, leaders adopting an evolutionary psychology approach to followership must do all they can to align followers’ goals with those of the organization and insure that the benefits people accrue outweigh the costs of working for the leader, as followers will either mutiny or leave if goals are misaligned or inequities are perceived.

However, social psychology tells us that something other than cost-benefits analyses may be happening when people choose to play followership roles. There are some situations where many people seem all too willing to abdicate responsibility and simply follow orders, even when it is morally offensive to do so. The famous Milgram experiments of the 1950s demonstrated that people would follow orders, even to the point of hurting others, if told to do so by someone they perceive to be in a position of authority. You would think the popularity of the Milgram research would subsequently inoculate people from following morally offensive or unethical orders, but a recent replication of the Milgram experiments showed that approximately 75 percent of both men and women will follow the orders of complete strangers whom they believe occupy some position of authority. Sadly, the genocides of Bosnia, Rwanda, and Darfur may be all too real examples of the Milgram effect. For leadership practitioners, this research shows that merely occupying positions of authority grants leaders a certain amount of influence over the actions of their followers. Leaders need to use this influence wisely.

Social psychology also tells us that identification with leaders and trust are two other reasons why people choose to follow. Much of the research concerning charismatic and transformational leadership shows that a leader’s personal magnetism can draw in followers and convince them to take action. This effect can be so strong as to cause followers to give their lives for the cause. The 9/11 terrorist attacks; the Mumbai, Bali, and London Tube bombings; the attempted bombing of a Delta airlines flight in December 2009; and suicide bomber attacks in Iraq and Afghanistan are examples of the personal magnetism of Oussama Bin-Laden and the Al-Qaeda cause. Although most people do not have the personal magnetism of an Oussama Bin-Laden or a Martin Luther King, there is a subset of people who can engender a strong sense of loyalty in others. Those with this ability need to decide whether they will use their personal magnetism for good or evil.

Trust is a common factor in the cost-benefits analysis, compliance with authority, or loyalty to leaders hypotheses. Put more simply, it is highly unlikely that people will follow if they do not trust their leaders. It can be very hard to rebuild trust once it has been broken, and followers’ reactions to lost trust typically include disengagement, leaving, or seeking revenge on their leaders. Many acts of poor customer service, organizational delinquency, and workplace violence can be directly attributed to disgruntled followers feeling betrayed, and the recent economic downturn has put considerable strain on trust between leaders and followers. Many leaders, particularly in financial services industry, seemed perfectly happy to disrupt the global economy and lay off thousands of employees while collecting multimillion-dollar compensation packages. Given the lack of trust between leaders and followers in many organizations these days, one has to wonder what will happen to the best and brightest followers once the economy picks up and jobs become more readily available. Because of the importance of trust in team and organizational performance, leaders need to do all they can to maintain strong, trusting relationships with followers.

A Framework for Followership

A final question or finding coming from the followership research concerns follower frameworks. Over the past 40 years or so researchers have developed various models for describing different types of followers. These models are intended to provide leaders with additional insight into what motivates followers and how to improve individual and team performance. When all is said and done the frameworks developed by these researchers have more similarities than differences, and a more detailed description of the Curphy-Roellig Followership Model can be found below.

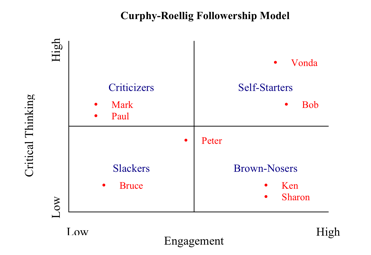

The Curphy-Roellig Followership Model builds on some of the earlier followership research of Robert Kelley, Ed Hollander, and Barbara Kellerman and consists of two independent dimensions and four followership types. The two dimensions of the Curphy-Roellig model are Critical Thinking and Engagement. Critical Thinking is concerned with a follower’s ability to challenge the status quo, identify and balance what is important and what is not, ask good questions, detect problems, and develop workable solutions. High scorers on Critical Thinking are constantly identifying ways to improve productivity or efficiency, drive sales, reduce costs, etc.; those with lower scores believe it is the role of management to identify and solve problems, so they essentially check their brains in at the door and not pick them up until they leave work. Engagement is concerned with the level of effort people put forth at work. High scorers are energetic, enthusiastic about being part of the team, driven to achieve results, persist at difficult tasks for long periods of time, help others, and readily adapt to changing situations; low scorers are lazy, unenthusiastic, give up easily, are unwilling to help others or adapt to new demands, and generally would rather be doing anything but the task at hand. Engaged employees come to work to “win” as compared to coming to work “to play the game.” It is important to note that engagement does not necessarily mean working 70-80 hours a week, as people can be highly engaged and only work part-time. What one does at work is more important than the number of hours worked, but generally speaking highly engaged employees tend to spend more time focusing on the challenges at hand than disengaged employees.

Self-Starters: Seeking Forgiveness Rather than Permission

As depicted in the graphic, the Curphy-Roellig model can be used to assess current followership types. Self-Starters, such as Bob and Vonda, are those individuals who are passionate about the team and will exert considerable effort to make it successful. They are also constantly thinking of ways to improve team performance, as they raise issues, develop solutions, and enthusiastically carry out change initiatives. When encountering problems, Self-Starters are apt to resolve issues and then tell their leaders what they did rather than waiting to be told what to do. This followership type also helps to improve their leaders’ performance, as they will voice opinions prior to and provide constructive feedback after bad decisions.

Self-Starters are a critical component of high performing teams and are by far the most effective followership type. Leaders who want to create these followers should keep in mind the underlying psychological driver of this type and the critical behaviors they need to exhibit if they want to create Self-Starters. In terms of the underlying psychological driver, leaders need to understand that Self-Starters fundamentally lack patience and are always thinking – in the shower, during a run or over their Saturday morning coffee. They do not suffer fools gladly and expect their leaders to promptly clear obstacles and acquire the resources needed to succeed. Leaders who consistently make bad decisions, dither, or fail to quickly secure needed resources or follow through on commitments are not apt to create Self-Starters. Self-Starters want to share their ideas real time and want quick feedback outside of the normal workday hours. It is very important for leaders wanting to create Self-Starters to articulate a clear vision, values and set of goals for their teams, as this type operates by seeking forgiveness rather than permission. If Self-Starters do not know where the team is going and what the rules are, then they may well make decisions and take actions that are counterproductive. And Self-Starters whose decisions get overruled too many times are likely to disengage and become Criticizers or Slackers. In addition to making sure they understand the team’s vision, values and goals, leaders also need to provide Self-Starters with needed resources, interesting and challenging work, plenty of latitude and regular performance feedback, recognition for strong performance, and promotion opportunities. The bottom line is that Self-Starters can be highly rewarding but challenging team members, and leaders need to be available, responsive and bring their A game to work if they want to maximize the value of these followers. It will be hard to provide Self-Starters all they crave in a normal work week, so being responsive 24X7 will help leaders demonstrate appreciation for their extra efforts.

Brown-Nosers: Seeking Permission Rather than Forgiveness

Brown-Nosers, such as Ken and Sharon, share the strong work ethic but lack the critical thinking skills of Self-Starters. Brown-Nosers are earnest, dutiful, conscientious, and loyal employees who will do whatever their leaders ask them to do. They never point out problems, raise objections, or make any waves, and do whatever they can to please their bosses. Brown-Nosers constantly check in with their leaders and operate by seeking permission, rather than forgiveness. As such, it is hardly surprising that many leaders surround themselves with Brown-Nosers, as these individuals are sources of constant flattery and tell everyone how lucky they are to be working for such great bosses. They can also create compelling rationale (“everyone is doing it”) to support taking actions that are inappropriate or unethical when observed in the sunshine of an objective setting. It may not be surprising to know that Brown-Nosers often go quite far in organizations, particularly those not having good objective performance metrics. Organizations lacking clear goals and measures of performance often make personnel decisions on the basis of politics, and Brown-Nosers work hard to have no enemies (as they can never tell who their next boss will be) and as such play politics very well.

Because Brown-Nosers will not bring up bad news, put everything in a positive light, never raise objections to bad decisions, and are reluctant to make decisions. As such, teams and organizations consisting of high percentages of Brown-Nosers are highly dependent on their leaders to be successful. There are several actions leaders can take to convert Brown-Nosers into Self-Starters, however, and perhaps the first step is to understand that fear of failure is the underlying psychological issue driving Brown-Noser behavior. All too often Brown-Nosers have all the experience and technical expertise needed to resolve issues, but they do not want to get caught making “dumb mistakes” and lack the self-confidence needed to raise objections or make decisions. Therefore, leaders wanting to convert Brown-Nosers need to focus their coaching efforts on boosting self-confidence rather than the technical expertise of these individuals. Whenever Brown-Nosers come forward with problems leaders need to ask them how they think these problems should be resolved, as putting the onus of problem resolution back on this type boosts both their critical thinking skills and self-confidence. When practical, leaders then need to support the solutions offered, provide reassurance, resist stepping in when solutions are not working out as planned, and periodically ask these individuals what they are learning by implementing their own solutions. Brown-Nosers should only be rewarded or recognized for observable positive results – it is extremely damaging if the organization perceives them as being rewarded for their sycophant behavior. Brown-Nosers will have made the transition to Self-Starters when they openly point out both the advantages and disadvantages of various solutions to problems leaders are facing or challenge a direction or position the leader is advocating.

Slackers: Working to Live versus Living to Work

Bruce and Peter are Slackers, as that they do not exert as much effort toward work, believe that they are entitled to a paycheck for just showing up, and it is management’s job to solve problems. Slackers are quite clever at avoiding work and often disappear for hours on end, make it a practice to look busy but get little done, have many excuses for not getting projects accomplished, and spend more time devising ways to avoid getting tasks completed then they would just getting them done. Slackers are “stealth employees” who are very content to spend the entire day surfing the Internet, shopping on-line, gossiping with co-workers, or taking breaks rather than being productive at work. Nonetheless, Slackers want to stay off their boss’ radar screens, so they often do just enough to stay out of trouble but never more than their peers.

Transforming Slackers into Self-Starters can be very challenging, as leaders need to improve both the engagement and critical thinking skills of these individuals. One interesting observation is that many leaders mistakenly believe Slackers have no motivation. It turns out that Slackers have plenty of motivation; the problem is their motivation is directed towards activity unrelated to work. This type of follower can spend countless hours on videogames, riding motorcycles, fishing, side businesses, or other hobbies, and if you ask them about their hobbies then their passion becomes quite evident. Slackers work to live rather than live to work and tend to see work as a means of supporting their other pursuits. Thus the underlying psychological driver for Slackers is motivation for work; leaders need to find ways to get these individuals focused on and exerting considerably more effort towards job activities. One way to improve work motivation is to assign tasks that are more in line with these followers’ hobbies. For example, assigning research projects to followers who enjoy surfing the Internet might be a way to improve work motivation. Improving job fit is another way to improve motivation for work. Many times followers lack motivation because they are in the wrong jobs, and assigning them to other positions within teams or organizations that are a better fit with the things they are interested in can help improve both the engagement and critical thinking skills of these individuals.

Leaders wanting to convert Slackers into Self-Starters also need to determine what role favoritism and the lack of needed resources are contributing to followers’ disengagement and uncritical thinking levels. It may well be that some Self-Starters lack the equipment, technology, or funding needed to perform well and have simply given up. In other cases leaders may be playing favorites and causing those not in the inner circle to quit making meaningful contributions.

At the end of the day the work still has to get done, and there are many times the leader does not have the flexibility to assign preferred tasks or new jobs to these individuals (or would want to reward them for substandard efforts). If followers have all resources they need to succeed and favoritism is not an issue, then leaders need to set unambiguous objectives, provide constant feedback about work performance, and then gradually increase performance standards and ask for inputs on solutions to problems. Because Slackers dislike attention, telling these individuals they have a choice of either performing at higher levels or becoming the focus of their leaders’ undivided attention can help improve their work motivation and productivity or cause them to objectively fail. Leaders should have no doubt, however, that converting Slackers to Self-Starters is a difficult and time-consuming endeavor and may not be doable. As such, leaders may find it much easier to replace Slackers with individuals who have the potential to become Self-Starters then spend time on these conversion efforts.

Criticizers: Finding Fault in Everything you do

The last of the four types, Criticizers, are followers who are disengaged from work yet possess strong critical thinking skills. But rather than directing their problem identification and resolution skills toward work-related issues, Criticizers are instead motivated to find fault in anything their leaders or organizations do. Criticizers make it a point of telling co-workers what their leaders are doing wrong, how various change efforts are doomed to failure, how bad their organizations are when compared to competitors, and how management shoots down any suggestions for improvement. These pessimistic individuals are constantly complaining, whining, and moaning about the current state of affairs. In terms of team and organizational performance, Criticizers are often the most dangerous of the four types, as they believe it is their personal mission to create converts. They are frequently the first to greet new employees and “tell them how things really work around here.” And because misery loves company, they tend to hang out with other Criticizers. If not effectively managed, Criticizers can take over teams and entire departments. Dealing with Criticizers can be among the most difficult challenges leaders face.

It turns out that some Criticizers are just immature or foster an unwarranted sense of entitlement, but most were once Self-Starters who became disenchanted because their strong critical thinking skills allowed them to identify where their leaders were acting inconsistently with articulated objectives, values or goals. More specifically, Criticizers can be acutely aware of and offended by recognition awarded to Brown-Nosers in the absence of any observable results.

Because they are motivated to create converts, Criticizers are like an organizational cancer. And like many cancers, Criticizers respond best to aggressive treatments. Leaders need to understand that the need for recognition or any breaches of trust are the key psychological driver underlying Criticizer behavior. Criticizers act out because they are mad and crave recognition. Some Criticizers were Self-Starters who got their recognition needs satisfied through their work accomplishments, but for some reason they were not recognized, awarded a promotion they felt they deserved, an organizational restructuring took away some of their prestige and authority, or they worked for a boss who felt threatened by their problem solving skills. Other Self-Starters became Criticizers when their leaders acted inconsistently with their articulated vision, values, and goals. Leaders will have no chance converting these latter individuals until they have the self-awareness to recognize and align the values they are asking from the organization with their own actions. With that foundation leaders can then begin the reconversion to Self-Starters by finding opportunities to listen to and publicly recognize these individuals. As stated earlier, Criticizers are very good at pointing out how decisions or change initiatives are doomed to failure. When Criticizers openly raise objections, leaders need to thank them for their inputs and then ask how they think these issues should be resolved. Most Criticizers may initially resist offering solutions, as they have drawers full of solutions that were ignored in the past and may be reluctant to share their problem solving expertise in public. Leaders need to break through this resistance and may need to press Criticizers for help. And once Criticizers offer solutions leaders can live with, leaders need to change and adopt these behaviors or solutions and publicly thank Criticizers for their efforts. Repeating this pattern of soliciting solutions, adopting suggestions, and publicly recognizing Criticizers for their efforts will go a long way towards converting this group into Self-Starters. If leaders make repeated attempts to engage Criticizers but they fail to respond, then termination is a viable option for this type. However, as they do so leaders should carefully look in the mirror and ask what they did to lose the hearts and minds of these good thinkers. Yet leaders who do not aggressively deal with these individuals may find themselves leading teams made up of nothing but Criticizers and eventually being asked to look for another job.

Implications of the Curphy-Roellig Followership Model

There are a number of aspects of the Curphy-Roellig Followership Model that are worth additional comment.

First, the model can help leaders assess follower types and determine the best ways to motivate their team members.

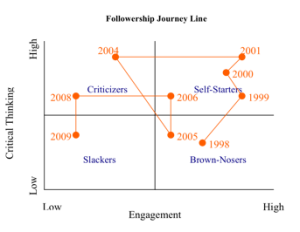

Second, leaders need to understand that followership types are not static; they can and do change depending on the situation. The above graphic depicts how one’s followership type changes as people switch jobs, inherit different bosses, were given different responsibilities, etc. This particular individual started their professional career as a Brown-Noser, moved up to become a Self-Starter, spent some time as a Criticizer, and is now a Slacker. When asked why their followership type changed over time, most people say their immediate boss was the biggest factor in these changes. Thus leaders have a very direct impact on effective followership—either by selecting direct reports with Self-Starter potential or developing direct reports into Self-Starters.

Third, because Self-Starters are the strongest contributors to organizational success and leaders have a direct influence on the followership types of their direct reports, there are several things leaders need to do in order to create teams of Self-Starters. Among them include setting clear expectations around engagement and critical thinking, role modeling the behaviors of Self-Starters, acting in a manner consistent with stated values, treating people fairly, creating an environment where people feel safe to offer solutions, clearing obstacles and providing needed resources, articulating a vision of the future, and holding staff members accountable for Self-Starter behavior.

Fourth, although there are thousands of training programs and books to develop leadership skills, there is little available to teach people how to be good followers. We believe that most people assume followership just happens and leaders are entirely responsible for creating effective or ineffective followers. The impact of leaders on followership cannot be denied, but we also believe organizations can train people how to be Self-Starters. Training program content would include the four followership types, what it takes to be a Self-Starter, and provide self and other feedback on the type currently being exhibited. Participants would also learn what they needed to do to become Self-Starters, such as how to identify problems, generate and present solutions, and how to get engaged and get things done at work. Training people on followership and having leaders who foster effective followership seem to be relatively easy ways to improve organizational effectiveness.

Fifth, organizations having decent selection processes are more likely to hire Brown-Nosers and Self-Starters than Criticizers and Slackers. Additional research has shown the longer people stay in organizations, the more likely they will be Criticizers. Over time people learn how to develop critical thinking skills in their functional expertise, be it accounting, logistics, education, etc. It is usually only a matter of time before these same critical thinking skills get directed at leaders, teams, and organizations. In addition, because employees carefully watch the actions and key decisions of their leaders (including who they hire, promote and reward), a Self-Starter’s critical thinking skills enable him or her to identify any misalignment with their leader’s actions and the articulated vision, values and goals and begin the slide toward the dark side of followership. That being said, teams and organizations populated with followers with high populations of Criticizers, Brown-Nosers and Slackers need to take a hard look at their leadership talent. Research shows that well over half the people in positions of authority are incompetent, and the Criticizer and Slacker followership types may be ways direct reports cope with clueless bosses, while Brown-Nosers will do very well in an environment where a boss values people who tell him or her how great he or she is.

Sixth, because people in positions of authority also play followership roles, they need to realize how their own followership type affects how they lead others. For example, leaders who are Self-Starters are likely to set high expectations, reward others for taking initiative, and give top performers plenty of latitude and needed resources. Leaders who are Brown-Nosers will squelch objections and demand that direct reports constantly check in. They will also expect their employees to do what they are told, not make waves, and be loyal lapdogs whose sole purpose in life should be pleasing their superiors. Leaders who are Slackers are laissez-faire leaders who are disengaged from work, unresponsive to followers’ requests, unavailable, and lead teams that get little accomplished. Leaders who are Criticizers will not only complain about their organizations, they can also direct their critical thinking skills toward employees. As such, these leaders tend to manage by exception and find fault in everything their followers do.

Concluding Comments

We started this article by stating that followers provide the “horsepower” to organizational performance and prompting readers to give more thought to effective followership. Leaders wanting to build high performing teams need to be aware of the important role followership plays in group dynamics and team performance. As a society we spend a lot of time and effort finding and developing leaders, but if the same attention was put on understanding and developing followers, then leaders would have to operate at a much higher level and their resulting impact would be significantly improved. As the world becomes more flat, technical, and professional, people will need to get more comfortable sliding back and forth between leader and follower roles. We believe the skills of identifying, developing, and fostering effective followership will be more important then ever in the past.

__________________________________________

Gordy Curphy is the President of Curphy Consulting Corporation, a leadership consulting firm based in St Paul, MN. Prior to starting his own business in 2003, Gordy was a Vice President and General Manager for Personnel Decisions International and an Associate Professor at the USAF Academy. Gordy earned his bachelor’s degree from the USAF Academy and his PhD in industrial and organizational psychology from the University of Minnesota.

Mark Roellig is the Executive Vice President and General Counsel of Massachusetts Mutual Life Insurance Company (“MassMutual”). Before joining MassMutual in 2005, Mark served as general counsel and secretary to the following three public companies prior to their sale/mergers: Fisher Scientific International Inc., Storage Technology Corporation (“StorageTek”) and U S WEST Inc. Mark received his bachelor’s degree in applied mathematics from the University of Michigan, earned his law degree from George Washington University, and his M.B.A. from the University of Washington.